- Home

- D. M. Fraser

Class Warfare Page 2

Class Warfare Read online

Page 2

—Clara Beers Blashfield, Worship Training for Primary Children

DON’T SING YET; we have a situation developing here. It’s a good night for situations, a good night for tramping about the streets, disturbing the peace. Midwinter drizzle, a smear of fog, this tubercular chill in the air: all the ancient, appropriate ingredients. By all means let’s look menacing, if we can; it shouldn’t be difficult, in these shadows … too bad there’s not a saxophone playing somewhere, just down the block. The lady would appreciate that. But never mind, here she comes now; button up that overcoat, buddy …

Perhaps she supposes it’s relief we’re after, a dime for coffee (only a dime?), a smoke, a mattress for what’s left of the night, spare change for bus fare or whatever else, a quick feel: the necessities, as we call them, of life. She suspects something will be asked for, perhaps humbly, apologetically (she hopes), more probably with force or threat of force, meanly: a Hey Lady in that tone of voice, you know the one, and what can she do, defenceless? She wouldn’t mind a bit of a thrill; no doubt it’s been a long, dull day; nothing ever happens in this town, this dead end of the world … We could do worse than to allow her a moment of fright, exquisite terror that’s in and out like a needle in the vein she’s been waiting years, a lifetime of satiety, to tap; after all, we’re not really dangerous. Are we? Evidently she’s not sure, right now. When it comes down to the event, to this altogether too specific instance, possibly she’d be just as happy—happier—to let it pass. If it will pass. At this point, it behooves us to be merciful. It behooves us not to insist. Let it pass. We can be desperate later.

And she’s gone, not too quickly, no clatter of delicate heels down this pavement: no telltale scurrying to accuse us. An exchange of mercies. Of course we’re suspicious characters, out like this in the sooty night, going nowhere profitable, when everyone knows all decent folk are home snug in their parlours watching the late movie. Of course. We can say (if queried): This is our late movie. Who’ll believe us? Not she, at least, swallowed up now behind her safe doorway, thankfully home in her lamp-lit room, her refuge (chintz curtains, lumpy bed, wax flowers in a Mexican vase), routinely taking off her brown coat, routinely thinking, or trying not to think, Jesus that was close. Was it mercy, or only habit, that let her go? There were other alternatives. There was no compulsion, surely, to deny magic its improbable hour. Tonight, if we dared, we could blast through the grey world’s walls, and who’d ever care? Who’d notice?

If we dared. It’s true no one would notice, much less care: they have other insurgencies than ours to trouble their nights. We’re not the fiercest skulkers they have to contend with, out here in the murk. Statistically, we’re hardly a scratch on their lens, a barely detectable anomaly at the bottom of the image, not anything worth paying heed to. That lady, now, the intended prey—by this time she’ll have stopped trembling, she’ll be taking off her makeup, putting on her Sleepytime Beauty Cream, sipping placidly at the vermouth she’s poured for her nerves, planning the letter she’ll write to her mother. “A weird thing almost happened tonight, but nothing came of it. Honestly.” Later she’ll set the alarm, climb between the daisy-patterned sheets, read a few pages of a Harlequin Romance (Edith Goodwell, Society Nurse), fall asleep to dream of her handsome cowboy, her clean-cut young intern, her gridiron hero … Something weird almost happened, but we were chivalrous, and as frightened as she.

Alternatives, yes. We could have spoken tenderly, in cultured voices, could have borne her off (on horseback?) to feed on poetry and sweet wine, tales out of a more gallant age than we’ve ever lived in, entertainments vouchsafed only to the secret princes of this world—to the princes we might have been, and their chosen ladies, those rescued out of the sooty night, not absolutely at random. And then we could have had, and well deserved, that old open-window-at-dawn adagio, rain in the streets articulate as fireworks, coherences of traffic, bells, stray scavenger birds, the first light. No. She never would have endured so far. Ol’ leadfoot Reality would have come clomping in, just at the radiant moment, to slam the window, turn up the lights, say, What the hell d’you think you’re doin’? Dumb broad. And that would have been the end of that.

And here we are, as always, the Heartbreak Kids in Nighttown, carrying on. We’re not required to do it; we could as easily be doing something else, any number of things (Name one); we could, since you ask, be off performing gainful employment on the graveyard shift. We could be making ourselves socially useful, reading serious literature, reawakening the dormant libido, preparing for the future. Other people do that, constantly, without unusual anxiety. The satisfactions of this night, as we discover them, are ephemeral; all the Official Wisdom tells us so. When I was a scholar, I studied the strangeness of the world. When I was a poet, I praised the strangeness in measured strophes. When I was a singer, I sang “Marching to Praetoria,” because I’d learned it as a child. When I was a child, I spake as a child, but when I became a man, I put away childish things. The strangeness is all around. No one is singing, so far. We can, we may as well, make an epic journey, anywhere that pleases us—down this street, around that corner, arms swinging, voices lifted up in vulgar celebration. There’s no one else in the street. I know I’m tempting you, letting in just a few riffs of the brass band, warm-up exercises, an aborted flourish of percussion, and if you’re not paying very strict attention, arms will begin to swing, step grow sprightly: any moment now. It’s begun that way before. One-two-three one-two-three. Men have gone mad in such circumstances. Do you imagine I haven’t heard them, singing “Marching to Praetoria” in cheerful paramilitary voices, striding along in cadence, mad, in the notorious middle of the night? Is it, for us, an ignoble precedent?

We are marching to Praetoria,

Praetoria, Praetoria

We are marching to Praetoria …

I know what you’re thinking: We’re just out for a walk, fer chrissake. On the empirical level, we’re just out for an evening stroll. And on the anagogical level? Huh? We must be going somewhere. Perhaps not Praetoria; we may never get to see that amber sunlight, breathe that dusty colonial air. And if not Praetoria, then probably not Wichita, or Galveston, or Santa Fe, the mythic cities. We’re not going, yet, to the source of the Ho Chi Minh trail, or to the outermost rocks of Tierra del Fuego, or the headwaters of the Nile, or the village of Main-à-Dieu, Nova Scotia, where in my fifteenth year I committed imperfect love among the lobster traps. But I’ll maintain that we’re bound somewhere, nonetheless: into this beer parlour, that café, the smoke-stained lobby of any of these hotels, a more local destination. Choose it. Seize the historical imperative. We can stumble through any of the available doors: to indulge in interesting perversions, play at petty larcenies, watch disreputable movies, overthrow the state. Everything is set up for us, everything is there. The world is full of strangeness.

That may be. No lack of diversions, anyway, out here in the life. Year after year, this life. It rattles on. Wears a man down, wears him out, he thinks: Time to get movin’, time to stop. Can’t stop, can’t get goin’. Sleep no good, never enough of it. Noise breaks in, voices always cursin’, wantin’ this or that, no end to it. Never ask where the good times went, they went away. I had a woman, used her well, made my life a livin’ hell. Had a buddy, bought him a drink, better thrown my money down the kitchen sink.

Had a vision

lost it at the zoo

a highly unintelligent

thing to do.

Maybe we should try walkin’ backwards for a while, at least we’ll find out where we’ve been.

Or we could simply stand still, each upon his appointed square of cement, and wait until somebody else decides (too late) what to do about us. With flashlights, uneasy eyes under shiny visors, hands poised at holsters, questions we could invent implausible answers to. “What’s the charge, officer?” “Conspiracy to commit existence.” We know how that would turn out, don’t we? We know in detail precisely how that would turn out.

Hell, I’m only talking to keep warm. Something appears to have gone wrong; the wind is biting; I can’t resist wondering if this is exactly what we were put in the world, wherever we are, to do. If the spark may not, at last, have expired, while we were looking at scenery. “The damp gets into the skin, puts out the fire,” I was told. To pass the time, change the subject, I nodded sagely. I have no patience with the speculations of the sane. We were sitting, my great-aunt Julia and I, in her fly-speckled living-room; the wallpaper was yellow, the drapes red velour; the smell was more or less lilac. “Beware, beware of the damp,” she said. “I tell you this for your eventual profit. Remember it, my child, when I’m dead and buried in the ground.” I did, too.

Don’t sing, that’s not the right tune. Think rather of cancer; recite the Seven Danger Signals; repeat the charming prayers of your vanished youth; declaim the Phaedo; move your lips silently, bitterly, in any species of imprecation, anything that comes to mind. Or, if you’re determined to sing, try this familiar carol:

God sees the little sparrow fall

and snickers up his sleeve

If that’s the way he treats the birds

I’m damned if I’ll believe.

One day we may well come to Praetoria, meet again in Praetoria, sip chilled lemon tea in Praetoria, in an embattled garden: and the wrath of the wretched centuries may consume Praetoria, may sink Praetoria into the blasted veldt, may flatten Praetoria and all its works into the imperial dust. We’ll meet in Praetoria, indeed, old drunk soldiers in scarred fatigues, rudely labelled pith helmets, prescription shades from Liberation Optical, and we won’t be welcome. There will be no welcome, for the likes of us, in Praetoria. We’ll just have to grin, shoulder our muddy kitbags, and strike out for home.

That’s one option. Another is high-stepping it down the street, toward us: another situation, it seems. Are we reprieved? Por favor, can we speak? She knows it’s the milky flesh we’re thinking of, the generous flesh, the unstartled eyes that follow and confess us. She knows, this one, that something can be taken, can even be offered, held out lightly, received as lightly: and in a twinkling, a Hey Lady, we would forget Praetoria forever. Why not? Let the band pack up its instruments, straggle off to wife and bed. Respite, now. We would forget the mythic cities: Wichita, Galveston, Santa Fe, Laramie, East Orange. We would forget the imperfect love. And the desperado stories we never found speech to tell, the lines of patient canny men moving in the jungle, the rocky hermitages at the world’s edge, the steaming rivers, the blond and windblown veldt, all of it, all this. It would go. And good riddance. We’d never need it again.

… She’s gone. That smile was kindly, as it went past. Mercury lamps blued the white coat, the white legs below, for an instant of seeing. For an instant of absurd love, something almost happened. Are you surprised it didn’t? She’s thinking, Poor fellows, poor fools, what do they want? The question will occur to her frequently, hereafter; one day the answer will suggest itself. It often does, in these cases. Meanwhile I’ll talk on, to keep warm, to keep moving, to keep us both occupied on this retreat, this advance. One-two-three one-two-three, ready now? We are marching to Praetoria, Praetoria, Praetoria. We are marching … to … Praetoria, Praetoria … Hooray!

MASTERPIECE AVENUE

JANEY AND AMBROSE and Spiffy and I live on Masterpiece Avenue, in the historic site; we have had invitations to move elsewhere, generous offers, but we have always refused them. It is a thing of some consequence, after all, to be where we are, to have stayed here. In times of restlessness, we take pleasure in this; we stumble trustfully through the barren opulent rooms, fondling woodwork, plaster, chimney tile, groping the scabrous face of history. Architecture, Ambrose said, is consolidation: first the projection of tangible things in imaginary space, then the rendering of intangible space in real substance. That seemed profound enough. It occurs to me now that I was eating a chicken sandwich at the time, that I could discern no taste in it, that in those days Ambrose was always talking, I was always listening.

Those days: a mousetrap for time, an intention that hid itself in the cobwebs, eyes bright and nose a-quiver, the moment we named it. Let’s make memories, Janey said. She has pale hair, educated nostrils, hepatitis, a mother in Miami. We make memories regularly. We are all waiting, stoically, for the arrival of the Past: without yesterday to refer to, how shall we recognize tomorrow? As I write, Janey is plucking her pellucid eyebrows. I have forgotten, if I ever knew, what “pellucid” is.

Our house, according to Ambrose, is a specimen of Gothic Revival, “somewhat corrupt.”

But how imprecise our language is, how misleading our common prepositions. We live, in fact, neither on Masterpiece Avenue nor—as Spiffy likes to say, being preternaturally British—in it; our address represents little more than a tactical concession to the Telephone Book, which for economic reasons eschews semantics. (For economic reasons, also, we have eschewed the telephone, but that is irrelevant.) To industry, we are Masterpiece Avenue: so be it. For myself, dogged purist that I am, the first choice would be near, combining as it does accuracy and mystery both, but the consensus of the house—arrived at not without introspection, not without intimations of rancour—has settled upon beside, as topographically more specific. So I must concur, albeit under protest: we live, the four of us, beside Masterpiece Avenue, thirty-two feet and half an inch north-northwest, in the historic site.

There are stories, which we prefer to disregard, of old iniquity in our domain: heathen practices, crimes of passion, conspiracies against the state. The national magazines remain intriguingly silent on the subject, a silence we interpret, variously, as discretion, ignorance, or lack of interest. From time to time we observe, through the wreckage of our hedge, elderly ladies in poetic headgear standing in an attitude which may be reverence, in front of the Plaque. We seldom complain: the Plaque is attached securely to the gatepost, on the outermost surface; it is thus exterior to us, and incidental. We are always safely within, usually out of sight. The gate is unlocked only on Delivery Day, once a week, when Ambrose, our largest and bravest, stands guard.

I have never read the Plaque, but Janey—a promiscuous reader—has; she remembers it as follows:

HISTORIC SITE

IN EIGHTEEN SOMETHING

SIR SOMEONE OR OTHER

DIED UPON THESE PREMISES

“Sweeter it be to walk in Grace

Than jest with the Devil face to Face.”

Myself, I am spared the burden of curiosity. Truth to tell, I find the poetic ladies at moments oddly pleasing, poignant, in the manner of an heirloom watercolour; and their devotions, if obscure and (not inconceivably) perverse, have for me an aspect of mute creaturely pathos essentially akin to that engendered by dime-store portraits of small doomed deer, at twilight, praising their Master in their ineffable woodland way. I am more afflicted with sentiment, sometimes, than my comrades suspect.

There is a danger in this, which I concede, which I am studying to forestall. We have ourselves become, in our fashion, a species of monument, an item in the history of the site. We have, then, a responsibility to the world, a duty to be, at all times, monumental. We do not belong wholly to ourselves. We are here on sufferance, by the grace of the Landmarks Commission, to provide “continuity, the sense of a still-viable tradition, an ongoing ambience.” So we are told, so we believe. It appears to be, in some context, a political function; Ambrose, in a fit of melancholia, once growled something about the “comprador class,” into which we may or may not have been “conscripted.” But we all know what Ambrose is like, when the fit comes on him.

In any event, our work is apparently serious, and we take it seriously. We are constrained to be outlaws, desperadoes, the stuff of an incipient mythology. My own weakness is that I am small and squirrelly, much given to moody brooding, inchoate inspirations (to violate the boundaries of our monumentality, embrace the poetic ladies, bare myself before the multitudes), and a not always manageable disposition to tears. Such behavi

our is not respected here; I must dissemble often; I await, with dread, the inexorable moment of self-betrayal. I am unworthy of Masterpiece Avenue.

Spiffy knows: I catch in her cool Angloid eye, in passing, a glint of—what? Recognition? Commiseration? Warning? And: We must all be careful, Ambrose whispers, polishing his glossy blade, nibbling wisely at his moustache. And whose toothpaste was it that spelled out, on the bathroom mirror one midwinter morning, the words of our sentence?—THIS IS A GOOD LIFE, WE ARE CONTENTED THEREWITH.

Is it? Are we? The issue arises, in despite of us, for we know the answer, we have rehearsed it often and well, and fear only that you who hear it, you who ask, will choose not to comprehend it. For our part, it would be merely redundant to ask: is it not our mission, is it not our job, to be contented? And why, all things considered, should we not be? We are friends, companions; we are schooled in loving kindness, we exchange affections, pleasant remarks, useful household articles, on a regular basis; we are tirelessly considerate, endlessly patient, tactful, benign. We sleep warmly in one bed, having no other and needing none; our protocols in this, as in all else, are democratic. We agree utterly upon all questions of ethics, music, the governance of this world, the ontological unnecessity for any other. Our blissful unanimity, being as it is complete and (we trust) indestructible, long ago eliminated any impulse to argument; consequently, in the seven years of our tenancy here, we have had neither cause nor occasion for dissension. Our lives have the texture and consistency of fine sculpture, a seemingly perfect harmony of line and mass. The Landmarks Commission would be proud of us, I think.

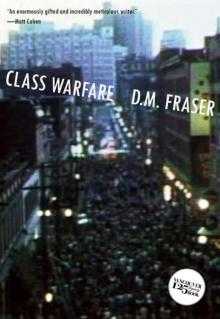

Class Warfare

Class Warfare